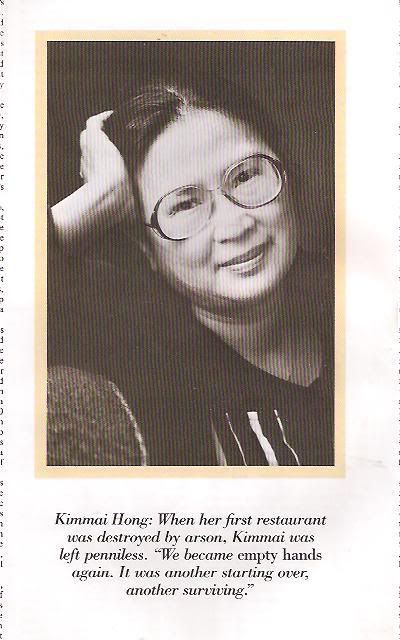

Pioneer In PassageTim Sills Kimmai Hong

Pioneer In PassageTim Sills Kimmai HongHue was, and perhaps still is, one of the most beautiful cities in Viet Nam. It was an ancient cultural center with a wallet citadel and dozens of exotic gardens. Much of the citadel was damaged when US Marines recaptured it from the Communists during the Tet Offensive of early 1968. The city was also well known for the long-haired women who wore the

ao dai , a light silk outfit of pants and blouse, covered in front and back by an outer dress, also silk, open at the sides from the ankles to the waist. The two garnments usually were in complimentary pastels, and the effect was stunning.

On the wall of Northwest Portland

Saigon Express restaurant is a painting of two such Hue girls pedaling bicycles on a forest path. They also wear the

non bai tho, a wide-brimmed conical hat , romantic poem concealed in it. Kimmai Hong is one of the refugee women still seen in an

ao dai . She is the owner of Saigon Express, and the artist who did the painting.

Kimmai says she is in her mid-forties, but she does not look middled-aged. The only lines on her face are

smile shadows at the corners of her eyes. When she speaks, she gestures with both hands, palm upturned, a Vietnamese symbol of giving. And she speaks softly, her eyes full of pensive depth. Looking at those eyes, one sees a person whose life is a tome of powerful drama.

Kimmai grew up in Hue and still wears her hair long. She majored in romance languages at the country's University of Saigon (Dai Hoc Van Khoa). Kimmai also was a student leader who protested government corruption. She married an obstetrician, worked as an independent importer, and wrote and published short stories and poetry.

Kimmai escaped from Saigon three years after the city's 1975 fall to the Communists. She'd made several previous attempts. Her husband was put in a "re-education camp" , a kind of Big Brother program set up by the Hanoi government for indoctrination and discipline of anyone suspected of disloyalty to the regime.

On a small boat packed with seventy-five other escapees, Kimmai left her homeland. She managed to bring along her four young children, but left behind not only her husband but also her research-scientist father, her mother, three brothers and five sisters. Her first home was a refugee center in Salem where she enrolled in English language and later in Computer Science. She did yard work on week-ends and picked berries with her children during the summer . "We were the first to get to the fields and the last to leave", she remembers.

After completing her studies, she worked for the State Of Oregon for three years as a computer programmer, meanwhile saving all she could in order to go into business for herself. In 1982 she opened The Blue Swans restaurant in Southeast Portland. One of the town's earliest Vietnamese eateries. It received rave reviews from the press. Less than two years later, the building was destroyed by arson. Kimmai, uninsured, was left penniless. "We became empty hands again", she says, "It was another starting over, another surviving ".

She was hired by Tektronix as a programmer analyst, and lived frugally once more in hope of starting a new restaurant. In mid-1985 she purchased the current site of Saigon Express. The atmoshphere there is identical to the small outdoor bijous of Saigon where the afternoon arts crowd congregated. Saigon Express is famous for its foods.

Last year, Kimmai's husband Hanh Pham appeared in Portland. He 's saved the life of a communist official's wife during childbirth, thereby gaining his freedom from both prison and VietNam. This was the beginning of further trials for the family, as Hanh was not allowed to practice obstetrics in Oregon, eventhough he 'd graduated from a medical school in Viet Nam. During his daily life in the United States, he suffered severe depression.

Kimmai now works seven days a week, sixteen to twenty hours each day to support her four children and a husband. She does virtually all the work at her business while Hanh is studying for medical exams.

"I love Viet Nam" she explains, fighting back tears. " I still feel a duty to my country "

"I teach my children Vietnamese", she says in her near-whisper. "And our traditions also. I do not want them to lose their values. There is so much opportunity in America, but there is also a great a need to know how to choose - about drugs, about being polite to adults and authorities, about respecting tradition, about sexual morality. I must always try to help my children understand : It is spirit first, not money."

Kimmai believes her many years of struggle have made her more independent than she would have been otherwise. She considers the exisgencies of survival to have carried her past all considerations of gender roles. "Now, after all this, I see myself as what we called

roseau, which is a very soft grass. The wind blows hard, and the grass bends far. After each storm, I stand back straight, never break".